Mere Christianity, The Abolition of Man, C. S. Lewis

The Deerslayer, The Last of the Mohicans, The Pathfinder, The Pioneers, The Prairie James Fenimore Cooper

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, That Hideous Strength, C. S. Lewis

The Philosopher's Stone, Colin Wilson

Blood & Thunder, Mark Finn (Robert E. Howard bio)

Renegades & Rogues, Todd B. Vick (Robert E. Howard bio)

Invisible Sun, Charles Stross

The Dragon Waiting, John M. Ford

The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane, Robert E. Howard

The Tremor of Forgery, Patricia Highsmith

The Elementary Particles, Michel Houellebecq

Whatever, Michel Houellebecq ]]>

Anyone related to Rahm Emmanuel is inherently not worth listening to but I remembered the above when I recently read Michel Houllebecq's book The Elementary Particles, which includes this quip:

Some people live to be seventy, sometimes eighty years old believing there is always something new just around the corner, as they say; in the end they practically have to be killed or at least reduced to a state of serious incapacity to get them to see reason.

That's much funnier!

]]>Upon This Rock, Book 3: Consider Pipnonia, David Marusek

The Dreaming Void, The Temporal Void, and The Evolutionary Void, Peter F. Hamilton

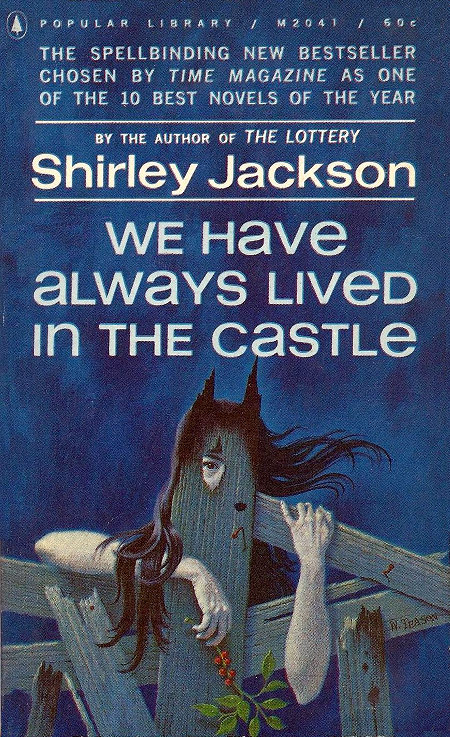

We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Shirley Jackson [review]

Redburn, Herman Melville

Pandora's Star and Judas Unchained, Peter F. Hamilton

The Gradual, Christopher Priest

The Evidence, Christopher Priest

The Hospital of the Transfiguration, Stanislaw Lem

The Invincible, Stanislaw Lem

Lavondyss, Robert Holdstock

White Fang, The Call of the Wild, and The Sea Wolf, Jack London

In the Ocean of Night, Across the Sea of Suns, Great Sky River, Tides of Light, Furious Gulf, and Sailing Bright Eternity, Gregory Benford

The Vicomte de Bragelonne, Ten Years Later, Louise de la Valliere, and The Man in the Iron Mask, Alexandre Dumas

Brighton Rock, Graham Greene ]]>

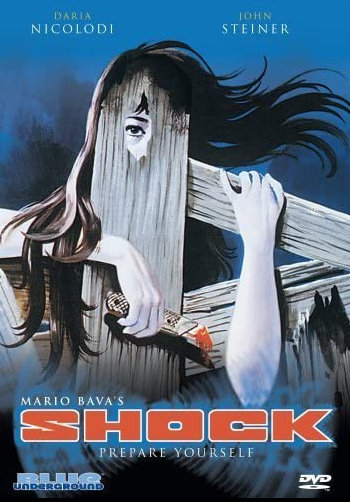

So memorable, in fact, that it was stolen for a 1977 Mario Bava film:

"Your honor, the replacement of the poisonous berries with a boxcutter makes this non-infringing, or in the alternative, permissible under the Fair Use doctrine."

]]>In the book:

1. Merricat Blackwood goes shopping in town Tues and Fri, not Tues only. (Why change that?)

2. Merricat has a private "Snakes and Ladders" type game that helps her cope with town visits. ["Crossing the street (lose one turn) came next, to get to the grocery directly opposite. I always hesitated, vulnerable and exposed, on the side of the road while the traffic went by."]

3. Local men in coffee shop: Jim Donell is the town Fire Chief (we don't learn this until the end of the book) and "Dunham" is a carpenter who did some work at the Blackwood estate. Donell wasn't involved romantically with Merricat's older sister Constance. Donell doesn't put out a cigarette in Merricat's coffee.

4. A central (past) incident, referred to throughout the story, is the poisoning of the Blackwood family at the dinner table six years earlier. Constance was accused and acquitted but is still blamed by the townspeople. Merricat had a brother, Thomas, among the murdered family members. Very little is said about him. Julian, uncle of Merricat and Constance, survived and still lives with the two sisters. "Uncle Julian" had a wife, Dorothy, who also died at the table that night.

5. Julian was sickened by the arsenic and shattered by the deaths and became an invalid thereafter. The book doesn't give his age but we assume late '60s. He is depicted as much older and frailer than Crispin Glover's interpretation of him in the film. Glover captures his intermittent sharpness of mind.

6. There is more detail about Julian's original position in the family. He and Dorothy were living under the roof of his brother John (Constance's and Merricat's father, one of the poisoned family members) and he was sensitive about his dependence. This was not helped by John, who kept an eye on how much food they ate at the table.

7. The book Merricat nails to the tree is a small ledger kept by her father of monetary sums owed to him and "people, he thought, who ought to do favors for him."

8. Nosy, pushy people circling around the house calling out for Constance, after the murders, is a regular occurrence. At first the sisters assume Charles is one of these.

9. Merricat doesn't go to town a second time for sugar. She is home with Constance (but upstairs) when Constance invites cousin Charles into the house.

10. Charles' father was Arthur Blackwood, John's brother. Arthur shunned Constance and Merricat after the murders, and Merricat spent time in an orphanage while Constance was on trial. Once Arthur was dead Charles was free to visit the sisters (or so he tells Constance). Charles also tells Constance that Arthur died broke.

11. Charles is hostile and sinister towards Merricat almost immediately. On his second day in the house he says to her (pretending to talk to her cat Jonas): "I wonder if Cousin Mary knows how I get even with people who don't like me?"

12. Merricat is our point of view character so we have to guess at conversations between Charles and Constance held outside her hearing. We know he's obsessed with the Blackwood family fortune, locked in a safe in the house, and that he's attempting to persuade Constance to get outside more and "do something" about the troublesome Merricat and addled Julian. There are no overt scenes of Charles romancing Constance or speaking Italian, as in the movie. That he might have been using sex for persuasion is hinted at near the end of the book. See item 22.

13. Mostly there is no sex; it's all absent, repressed. Charles embodies the threat of maleness to the feminized household but is not a Lothario.

14. The "Merricat should never be punished" scene takes place in the estate's abandoned summerhouse. Merricat imagines the entire family sitting around the dinner table agreeing that she should never be punished. It's a fantasy but also, possibly, in some sense, a flashback. Perhaps Merricat was spoiled as a child, so badly that she never developed a conscience. Jonathan Lethem speculates about this in his afterward to the Penguin edition.

15. Charles keeps insisting that Merricat be punished for pouring water on his bed and spreading dirt and leaves around his room. He never touches her. The scene of him angrily manhandling her on the stairs, and the suggestion that the sisters are flashing back to similar parental abuse, are completely invented in the movie.

16. At the climax, after the fire is out, Donell throws the first rock through a window and the townspeople invade the house, destroying furniture and valuables. The sisters try to escape into the woods; they are surrounded and heckled but not touched. Constance keeps Julian's shawl over her face so no one can see her. The grabbing and manhandling of the sisters never happens in the book.

17. Charles keeps yelling for people to get the safe out of the house. He doesn't try to break into it, as in the movie.

18. No dramatic gunshot stops the heckling. The doctor announces Julian has died. Charles (who seems to have joined the mob) wants to know if "she" killed him. The doctor says it was a heart attack. (Not suicide by smoke inhalation as suggested in the movie.) The mob disperses because a death has occurred.

19. The catalog of destruction to the house goes on for several pages. This is shown in the movie in a series of shots of furniture, dishes, etc being smashed. The book emphasizes the sadistic, systematic thoroughness of the destruction. (Silverware removed from drawers and bent, Constance's harp thrown out a window, etc.)

20. The life of the sisters, post-fire, is very primitive. All their clothes are burned. Constance makes herself a garment out of an old suit of Julian's. She makes a dress for Merricat out of a red and white checked tablecloth. They wall themselves into the house, which becomes overgrown with vines.

21. Charles comes back to the house once. He tries to trick Constance into coming out so his friend can get a photo for the magazines. He is still obsessing about the money in the house. He stands in the driveway yelling but the sisters don't acknowledge him. (In the movie he enters the house, attacks Constance, and is killed by Merricat.)

22. After several years (?) of living as shut-ins, the sisters hear some furtive movements outside the derelict house one night. They muse that their property might have to be renamed Lover's Lane. Merricat cracks, "after Charles, no doubt." Constance replies, "The least Charles could have done was shoot himself through the head in the driveway."

23. The poisoning of the family is never openly explained. There is no subtext of child abuse or sexual abuse, as in the movie. Just hints that patriarch John was a controller and a snob and the family was hidebound in its class assumptions and conventionality. We're left to assume that spoiled child Merricat was starting to find her family disagreeable (12 is pretty old to be sent away from the table without dinner) and planned the murders in a way that spared Constance. The book is a tale of co-dependency: Constance protects Merricat and neither show remorse for the killings. The movie adds motivation of an abusive parent because all Hollywood films must have an abusive parent as a villain.

The main change is to make the antagonist, Charles Blackwood, a nastier piece of work. In the movie he openly romances his first cousin Constance and physically grabs and pins down her sister Merricat, the 18 year old, in a moment of anger. In the book, the romance is buried to the point of invisibility and there is no grabbing. As with all Hollywood films today, there is the obligatory suggestion of parental violence or abuse. Jackson depicts John Blackwood, the dead father of Constance and Merricat, as a controller and a snob but not necessarily an abusive monster.

The motive for the book's central crime -- the unsolved poisoning of John and several family members -- isn't explicitly given in book or movie but the film's climactic staircase scene makes the suggestion that Charles' grappling with Merricat has awakened memories of similar behavior by John. it's implied in the reactions and facial expressions of the sisters during Charles' attack; Merricat even yells out "Father! Stop!" It makes the movie seem more powerful but it isn't Jackson's story; in the novel the reader has to decide who the monster is.

Shirley Jackson was a committed wife and stay-at-home mother of four whose feminism came out in her strong, complex writing. Passon's film version is also strong but leans to less complex, woke explanations for the characters' behavior. Possibly it's the only way to get a film made today.

]]>By Wallace Stevens

After the leaves have fallen, we return

To a plain sense of things. It is as if

We had come to an end of the imagination,

Inanimate in an inert savoir.

It is difficult even to choose the adjective

For this blank cold, this sadness without cause.

The great structure has become a minor house.

No turban walks across the lessened floors.

The greenhouse never so badly needed paint.

The chimney is fifty years old and slants to one side.

A fantastic effort has failed, a repetition

In a repetitiousness of men and flies.

Yet the absence of the imagination had

Itself to be imagined. The great pond,

The plain sense of it, without reflections, leaves,

Mud, water like dirty glass, expressing silence

Of a sort, silence of a rat come out to see,

The great pond and its waste of the lilies, all this

Had to be imagined as an inevitable knowledge,

Required, as a necessity requires.

via Poetry Foundation and Andrew Goldstone

I always forget about Stevens, a glacially-cold Modernist who hasn't been de-canonized by Wokesters yet because his writing is so opaque (don't worry, they'll get to this lawyer and insurance company executive eventually). The poem above is at once achingly melancholy and arch. "Silence of a rat come out to see" -- an eerie phrase. One could be forgiven for not getting past the first stanza, where his "savoir" brings reading to a dead stop. Possibly it's a synonym for "knowledge," but it's a verb in French and not usually unaccompanied by "faire" or "vivre" in English. This deliberate land mine puts the reader into a questioning frame for the remainder, as he or she lurches from unexpected simile to incongruous line break, to eventually contemplate The Great Pond.

]]>Jim Aikin (ed.), Power Tools for Synthesizer Programming

Tim Barr, Techno: The Rough Guide

Tim Barr, Kraftwerk: From Dusseldorf to the Future (with Love)

Brian Belle-Fortune, All Crew Muss Big Up: Journeys Through Jungle Drum & Bass Culture

Sean Bidder, House: The Rough Guide

Pascal Bussy, Kraftwerk: Man, Machine and Music

Pascal Bussy and Andy Hall, The Can Book

David Byrne, How Music Works

John Cage, A Year from Monday

Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen

Chris Cutler, File Under Popular

Kodwo Eshun, More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction

Bruce Gerrish, Remix: The Electronic Music Explosion

Peter Hammill, Killers, Angels, Refugees

Eric Hawkins, The Complete Guide to Remixing

Chris Kempster (ed.), History of House

Colin Larkin, The Virgin Encyclopedia of Dance Music

Simon Reynolds, Generation Ecstasy

Simon Reynolds, Retromania

Curtis Roads, Microsound

Ira L. Robbins (ed.), The Trouser Press Guide to New Wave Records

Mark Roberts, Rhythm Programming

David Rosenboom, Biofeedback and the Arts: Results of Early Experiments

R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape

Peter Shapiro, Drum'n'bass: The Rough Guide

Peter Shapiro (ed.), Modulations: A History of Electronic Music: Throbbing Words on Sound

Dan Sicko, Techno Rebels: The Renegades of Electronic Funk

Rick Snoman, The Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys and Techniques

Allen Strange, Electronic Music: Systems, Techniques, and Controls (2nd ed.)

David Toop, Rap Attack #3

David Toop, Ocean of Sound: Aether Talk, Ambient Sound and Imaginary Worlds

Nigel Trevena, Lou Reed & The Velvets

Tony Verderosa, The Techno Primer: The Essential Reference for Loop-Based Musical Styles

David Walley, No Commercial Potential: The Saga of Frank Zappa & The Mothers of Invention (original and updated editions)

Marc Weidenbaum, Selected Ambient Works Volume II (33 1/3 series) ]]>

A. Artist (alphabetical by last name)

1. Book about artist

2. "Artist's book"

3. Catalog of single artist exhibition

4. Artist biography

5. Book of artist interviews

6. Book of artist writings (e.g., Robert Smithson, Vassily Kandinsky)

7. Documentation of artist projects (e.g., Claes Oldenburg Store Days)

B. Exhibition (alphabetical by exhibit title)

1. Catalog of group show

2. Catalog of "theme" show

3. Auction catalog

C. Book about art (alphabetical by author)

1. Theory

2. Survey

3. Essay collection

4. How-to guide

5. Journalism (e.g., Naked by the Window)

D. Periodical (alphabetical by publication title, chronological within publication)

1. Magazine

2. Zine

3. Gallery guide

4. Directory (e.g., AiCA annual list of art critics)

The Three Musketeers, Alexandre Dumas

Twenty Years After, Alexandre Dumas

Aurora Rising and Elysium Fire, Alastair Reynolds

Divergence, C.J. Cherry (please, no more Foreigner books -- Cherryh has forgotten the value of an "antagonist" in moving the plot forward)

The Green Brain, Frank Herbert (screams "mid 1960s")

Thorns, Robert Silverberg (screams "early to mid 1960s" even though written later)

Revenger, Shadow Captain, and Bone Silence, Alastair Reynolds

A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens

Several ebooks by contemporary NYC writer Zak Zyz: Hawks at the Diner, Xan & Ink, The Master Arcanist, The Right to Bear Arms, and Survival Mode

The Cook, Harry Kressing (hat tip JS)

The Confessions of Arsène Lupin, Maurice Leblanc

The Ministry of Fear, Graham Greene ]]>