In a previous post we noted that Geert Lovink's response to the question, how can social media be used in education? was that it can't. Now he has a post up where the same question is asked about the arts, and gets the same response.

Max Ryan: Art involves a great deal of interpretation, so how does the gallery’s presence on Facebook or other social platforms enable visitors to voice their own interpretations about art and what does this add to an understanding of the work? How is artistic interpretation benefited through comment culture?

Geert Lovink: It doesn’t. Art galleries cannot compensate for the current poverty of the dominant social media platforms that were neither built to expand on details and provide insight nor to spark debate beyond likes and short remarks. Social media platforms as we know them are deeply commercial ‘machines of loving grace’ that aim to provide other machines with valuable data (clicks on adds etc.). The arts are not operating outside of the ‘clickbaiting’ mechanism. The museum sector is completely part of the advertisement ecology in which Google and Facebook play a dominant role.

It's refreshing to read this naysaying after Rhizome's attempt to shame us into using Facebook. Can thoughtful discussions be had on Facebook and Twitter about art, ones that preserve a record of the back-and-forth discussion, so that a year, two years, or six years later, a fair consensus can begin to emerge? No, they can't.

MR: Does the ‘openness’ to external voices exemplify democracy in action or just the rhetoric of tech companies when taking place on social media?

GL: There is no ‘openness’ whatsoever. Social media were not designed to foster debate. All they do is ‘monitor’ short exchanges and impressions. The platforms are used as measurement tools in marketing campaigns. The related ad firms in the background measure likes and retweets and clicks and sell these data profiles to third parties. It does not matter what people say on Facebook or Twitter, and the actual work on social media has been delegated to interns inside PR departments. There are large offices that do the ‘twittering’ for celebrities and CEOs and give constant feedback about the latest ups and downs.

And

MR: In an interview John Stack, the former head of digital transformation at the Tate, said it was the responsibility of the museum to go to where the audience is and prompt conversation online. They saw the where as existing on social media platforms. What do you think of the idea of social media as a discursive space? Can it exist in the same way that is associated with arts spaces? Does the context of the platforms effect this?

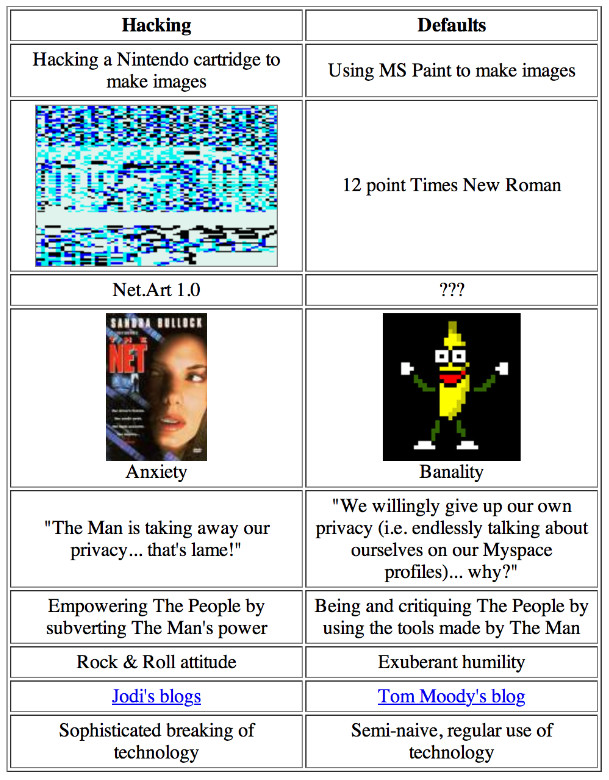

GL: Social media as we know them right now are not discursive machines. The internet in general might be, in theory, but the current social media architectures do not facilitate extensive exchanges. There is a historical reason for this. Social media grew out of a specific part of web culture of the blogs, in the early 2000s, after the baroque and excessive dotcom period of e-commerce had fallen to pieces. Social media picked up on the ‘updating’ part of blog culture, and stripped off the content bit. There is a reason why Twitter is limited to 140 characters. There was no technological limitation (not enough bandwidth, computing power, interface etc.).* The same can be said of Facebook’s aversion to discussion and debate. For a good decade already Facebook has been repressing the user’s need for community tools. There is no value in it for them. People need to like and share, say something fast and move on.

The arts do not need quick responses but thorough reflection and then debate about the positions people have formulated. Criticism presumes careful observation. This is then filtered through a rich vocabulary which every discipline has developed over the past decades and even centuries. Believe it or not, this even exists in the case of the internet...

What's needed is long-form writing (with illustrations and diagrams) that stays up reliably in one place for a few years. That's all we ask. Instead we get "shifting sand land."

*See addendum