Houston painter Perry House died in July 2020. He had a long, productive career and will be missed. Back in the '90s I reviewed his show at Davis/McClain gallery for Artforum and later organized an exhibition of his paintings at Gray Matters in Dallas. The Artforum review appears in text form below with a couple of minor tweaks to restore my original wording.

My Gray Matters essay [PDF] waxed more enthusiastic than the one below. For the magazine I wanted to champion a Texas artist lesser known in NYC so I indulged in some procatalepsis, anticipating questions that I felt would arise in a less nurturing critical environment. Whereas catalog writing is typically more boosterish.

A struggle I had with Artforum early on was over what image to use. I had sent a print of The Curtain, The Ship of Fools to accompany the review and then someone at the magazine contacted the gallery to request additional images. Possibly the art director's convenience in laying out pages guided image choices as much as any critical judgment, but it was annoying that they ultimately ran an image of work that I had criticized! (The editor later apologized for this.)

Houston Reviews, November 1992

Perry House

DAVIS/MCCLAIN GALLERY

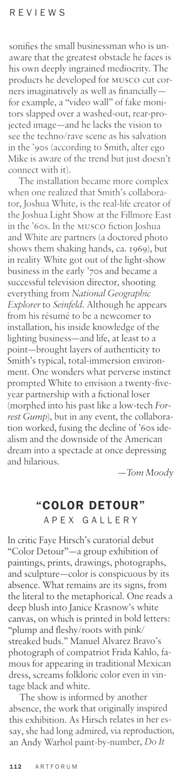

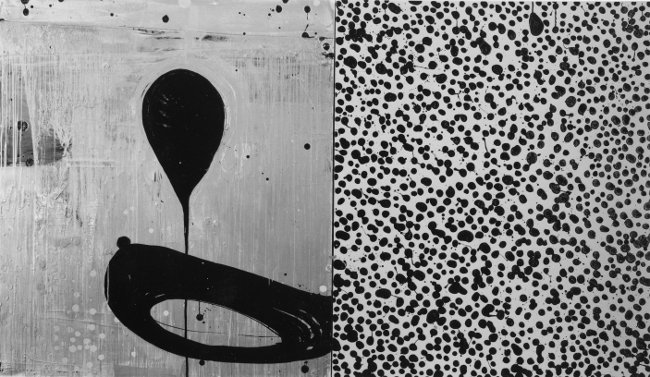

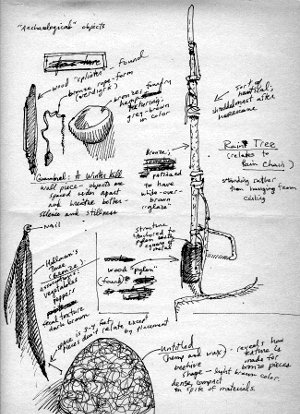

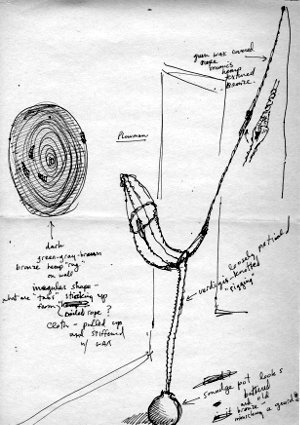

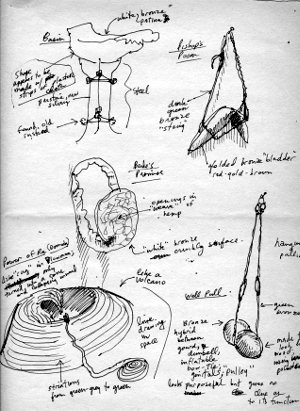

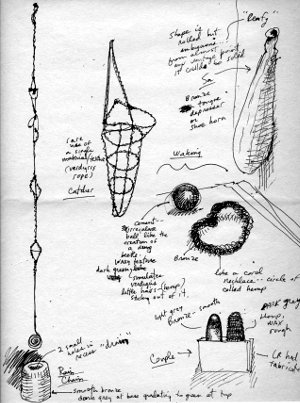

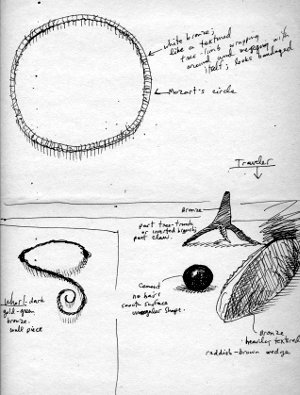

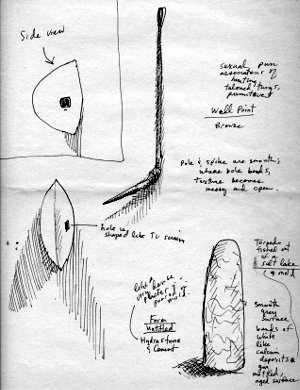

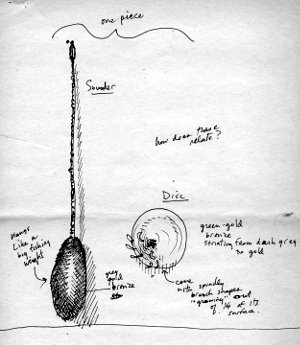

Perry House bases his paintings on an assortment of recurring motifs he calls his “cast of characters,” shapes that combine aspects of sculpture, furniture, architecture, and everyday objects, many of which symbolize the artist’s past experiences. The names assigned to these motifs (“The Ball,” “The Throne/Chair,” “The Cash Register,” and so on) are individually mundane but cumulatively poetic; their obsessive reappearance as images in paintings—isolated, abstracted, or fused with quasi-Modernist patterns—gives them a talismanic power.

This vocabulary of private symbols could be pretentious were it not for House’s sense of humor, vented through confidently eccentric brushwork and a caricaturist’s knack for exaggeration: the crisscrossing stripes receeding into space in The Screen, 1991, for example, suggest a minimalist grid formation enacted by a regiment of night crawlers. Similarly, the scrollwork pattern that crops up in many paintings might be as romantic as the Old South wrought-iron decor it recalls—if one overlooks the fact that the scrolls bulge and undulate like creatures in a Fleischer Brothers cartoon. Equally deflating is House’s handling of paint. Eschewing oils as “too seductive,” he badgers acrylics into messy, anxious life, turning their uninspiring pastiness into something resembling a virtue. A surface complexity arises partly from rampant overpainting: beneath each final coat, the textures of obliterated images continue to assert themselves.

House recently declared his intent to explore “the fine line between humor and horror, and to reestablish mass and volume in abstract painting in the most severe manner.” The former aim suggests a modest sort of content; the latter, perhaps, a Johnny-come-lately challenge to the formalist mandate of flatness. Fortunately the artist’s penchant for thematic understatement doesn’t get in the way of his painting. House’s work hints at George Condo’s irreverence and Ross Bleckner’s personalization of the impersonal without becoming derivative. In The Curtain, The Ship of Fools, 1991, a faux-romantic “character” floats against a field of intense blue, sandwiched between black and white curtains of Op art stripes-cum-scrollwork. This might be Condo’s version of Bleckner, or it might not; given the geographic and contextual distance between Texas and New York (and given the position of the painting within House’s own oeuvre), it’s probably sufficient to say that it represents the high-water mark of a parallel lineage. A more meaningful precedent, of course, would be the late work of Philip Guston, who paved the way for many painters to question, even mock, painting, while zealously continuing to pursue it.

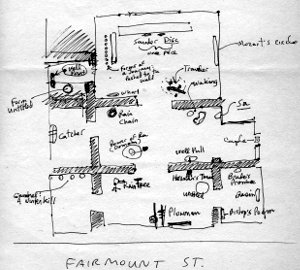

In addition to exhibiting a group of superb paintings on canvas and paper, House arranged a row of painted sculptures on the carpeted floor of the gallery, maquettelike constructions depicting his entire cast of characters. Though these quirky objects made a certain kind of sense against the grimy concrete floor of the artist’s studio, when they were expected to command a major portion of the gallery’s slick space they looked merely academic, especially in contrast to paintings that are anything but that.

—Tom Moody