|

|

PUBLISHED REVIEW

This was my first Artforum review and I was fairly happy with it. The editor (I assume Jack Bankowsky, who was reviews editor at the time) tightened up my prose, substituting formal words for some of my more casual phrasing (and added two "indeeds" that weren't in my draft). Normally the practice in the early 1990s was for editors to call the writer, read the piece through, and discuss changes. For my first two reviews I didn't get a call and several inaccurate descriptions of Ridgway's work went in. The "author's cut" of the review below corrects these errors.

Dallas Reviews, Artforum, October 1991

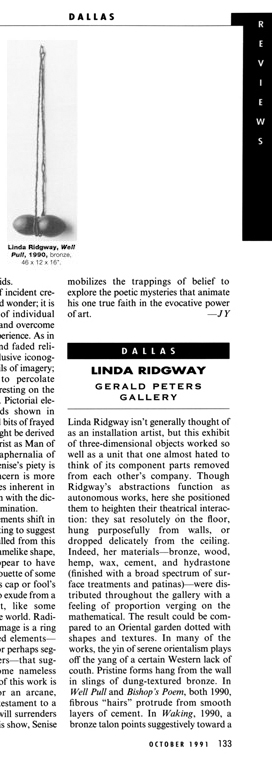

Linda Ridgway

GERALD PETERS GALLERYLinda Ridgway isn’t generally thought of as an installation artist, but this exhibit of three-dimensional objects worked so well as a unit that one almost hated to think of its component parts removed from each other’s company. Though Ridgway’s abstractions function as autonomous works, here she positioned them to heighten their theatrical interaction: they sat resolutely on the floor, hung purposefully from walls, or dropped delicately from the ceiling. Indeed, her materials—bronze, wood, hemp, wax, cement, and hydrastone (finished with a broad spectrum of surface treatments and patinas)—were distributed throughout the gallery with a feeling of proportion verging on the mathematical. The result could be compared to an Oriental garden dotted with shapes and textures. In many of the works, the yin of serene orientalism plays off the yang of a certain Western lack of couth. Pristine forms hang from the wall in slings of dung-textured bronze. In Well Pull and Bishop’s Poem, both 1990, fibrous “hairs” protrude from smooth layers of cement. In Waking, 1990, a bronze talon points suggestively toward a punctured disk jutting from another work (Well Point, 1991). In each of these, the bombastic and the stately were dramatically wed.

Ridgway commands, but never flaunts, an impressive range of techniques; indeed, her handling of difficult substances and processes is so understated that viewers might almost have missed the fact that this show consisted of one virtuoso technical feat after another. Under her control, bronze becomes malleable, a material to be spun into spidery filaments or compacted into dense clumps; so transformed, it seems light-years distant from the stench and sweat of the foundry. In Plowman, 1990, the metal takes on strikingly different aspects: a battered pot, a tightly coiled mat, or an elegant line drawing in space.

Though I referred to Ridgway’s works as abstractions, the designation is not entirely fair; perhaps “abstract-plus” would be more accurate. Some of her pieces recall tools but, like archaeological artifacts in various stages of restoration, their original function is lost to us. Other objects, such as Hullman’s Three, 1990, with its tapering, fingerlike pods of rough bronze, might be vegetables that have managed to evade the watchful eye of the taxonomist. Still others evoke comparisons to immediately recognizable phenomena, as in Power of Ra (Domain), 1990-91, where a verdigris-tinted bronze cone suggests the action of a volcano, its peak collapsing into a crater, as a rivulet of bronze lava trickling down its slope. Nevertheless, in every case, shorthand descriptions of the works -- leaf, bracelet, basket, bullet, plumb bob -- seem inadequate as soon as they are uttered. Ridgway’s objects are signifiers sans signifieds, steadfastly deflecting attempts to label them while consistently inviting us to try. —Tom Moody

AUTHOR'S CUT

Dallas Reviews, Artforum, October 1991

Linda Ridgway

GERALD PETERS GALLERYLinda Ridgway isn’t generally thought of as an installation artist, but this exhibit of three-dimensional objects worked so well as a unit that one almost hated to think of its component parts removed from each other’s company. Though Ridgway’s abstractions function as autonomous works, here she positioned them to heighten their theatrical interaction: they sat resolutely on the floor, hung purposefully from walls, or dropped delicately from the ceiling. Indeed, her materials—bronze, wood, hemp, wax, cement, and hydrastone (finished with a broad spectrum of surface treatments and patinas)—were distributed throughout the gallery with a feeling of proportion verging on the mathematical. The result could be compared to an Oriental garden dotted with shapes and textures. In many of the works, the yin of serene orientalism plays off the yang of a certain Western lack of couth. In Well Pull and Bishop’s Poem, both 1990, pristine forms hang from the wall in slings of dung-textured bronze. In Waking, 1990, fibrous “hairs” protrude from smooth layers of cement and wax. In Well Point, 1991, a bronze talon points suggestively toward a punctured disk jutting from the wall. In all of these, the rough and the stately were dramatically wed.

Ridgway commands, but never flaunts, an impressive range of techniques; in fact, her handling of difficult substances and processes is so understated that viewers might almost have missed the fact that this show consisted of one virtuoso technical feat after another. Under her control, bronze becomes malleable, a material to be spun into spidery filaments or compacted into dense clumps; so transformed, it seems light-years distant from the stench and sweat of the foundry. In Plowman, 1990, a multi-part work, the metal takes on strikingly different aspects: a battered pot, a tightly coiled mat, or an elegant line drawing in space.

Though I referred to Ridgway’s works as abstractions, the designation is not entirely fair; perhaps “abstract-plus” would be more accurate. Some of her pieces recall tools but, like archaeological artifacts in various stages of restoration, their original function is lost to us. Other objects, such as Hullman’s Three, 1990, with its tapering, fingerlike pods of rough bronze, might be vegetables that have managed to evade the watchful eye of the taxonomist. Still others evoke comparisons to immediately recognizable phenomena, as in Power of Ra (Domain), 1990-91, where a verdigris-tinted bronze cone suggests the action of a volcano, with its peak collapsing into a crater and a rivulet of bronze lava trickling down its slope. Nevertheless, in every case, shorthand descriptions of the works -- leaf, bracelet, basket, bullet, plumb bob -- seem inadequate as soon as they are uttered. Ridgway’s objects are signifiers sans signifieds, steadfastly deflecting attempts to label them while consistently inviting us to try. —Tom Moody