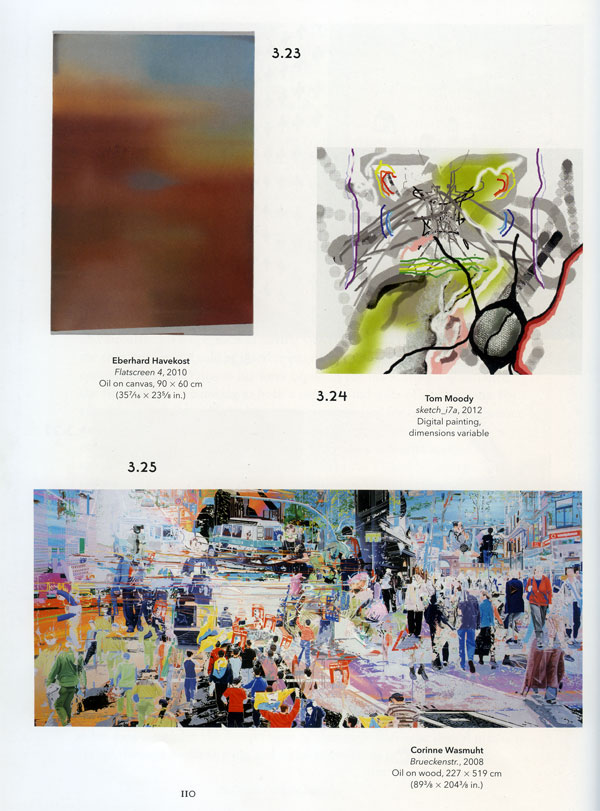

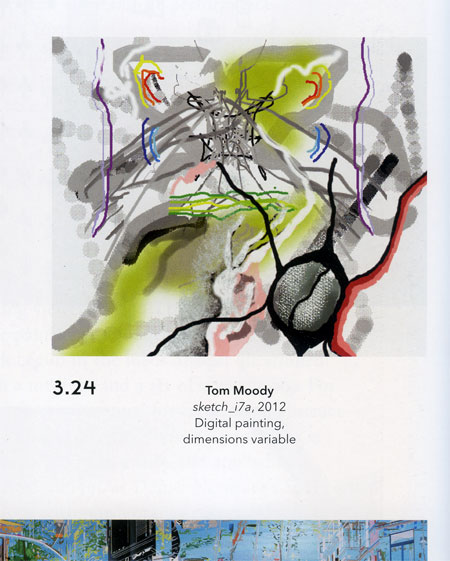

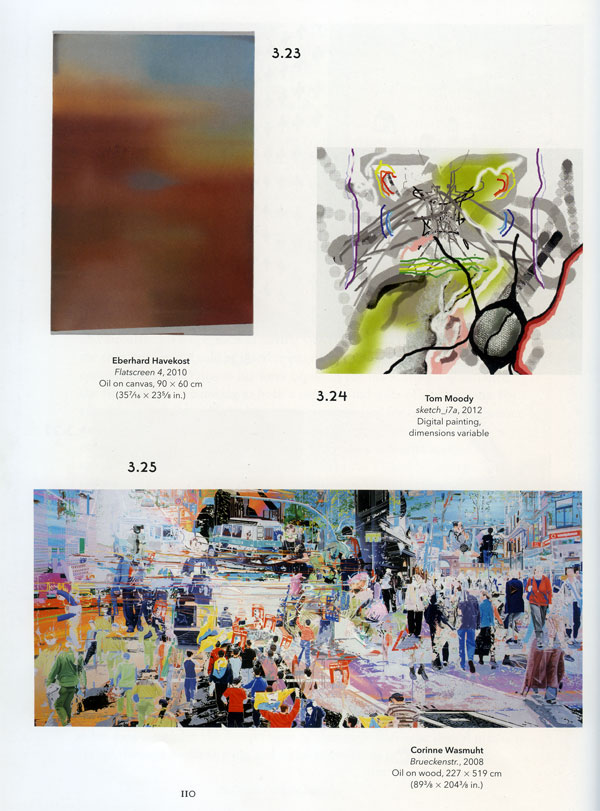

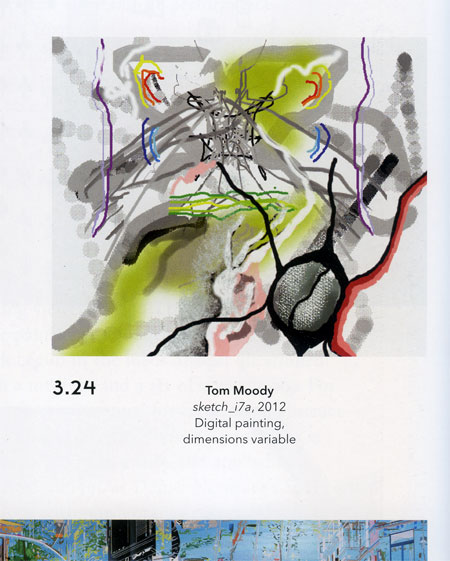

Above are scans of my work as it appears in the book Painting Now, by Suzanne Hudson, published last month. More about the book here. These scans are a bit clearer than my friend's in-store documentation, amusing as that gesture was (to some).

Above are scans of my work as it appears in the book Painting Now, by Suzanne Hudson, published last month. More about the book here. These scans are a bit clearer than my friend's in-store documentation, amusing as that gesture was (to some).

The 1971 Town Hall panel where Germaine Greer gave the speech below was a stunt organized by Norman Mailer to capitalize on his bad-boy reputation with the nascent women's movement. He published "The Prisoner of Sex" in Harpers and the conceit of the panel was that he would duke it out verbally with four female antagonists. Kind of a polygamist version of the later Bobby Riggs/Billie Jean King tennis match.

Despite the hokey premise, the "Town Hall" panelists took the subject matter seriously, and Greer's presence, voice, and arguments are electrifying (she is a great public speaker to this day). One inclined in 1971 to view the women's movement as strident might actually have been persuaded by the non-gendered tack of her rhetoric, which questioned the capitalist idea of winning, mocked Freud's view of the artist as a striving neurotic, and championed a self-effacing, collective art (a critique as relevant as ever in an era of rampant selfies taken for someone else's profit). Yet the noble hope of transcending Darwinism and ego had almost no correlation to real life, as we'll see below in a discussion of a court case over the rights to the panel's content.

Here is the speech again, with interruptions for commentary:

I'm afraid I'm going to talk in a very different way possibly than you expected. I do not represent any organization in this country and I dare say the most powerful representation I can make is of myself as a writer, for better or worse. I'm also a feminist and for me the significance of this moment is that I'm having to confront one of the most powerful figures in my own imagination, the being I think most privileged in male elitist society -- namely the masculine artist, the pinnacle of the masculine elite.

Bred as I have been and educated as I have been, most of my life has been most powerfully influenced by the culture for which he stands, so that I'm caught in a basic conflict between inculcated cultural values and my own deep conception of an injustice. Many professional literati ask me in triumphant tones, as you may have noticed, what happens to Mozart's sister?

However they ask me that question, it can have caused them as much anguish as it has caused me because I do not know the answer and I must find the answer. But every attempt I make to find that answer leads me to believe that perhaps what we accept as a creative artist in our society is more a killer than a creator, aiming his ego ahead of lesser talents, drawing the focus of all eyes to his achievements, being read now and by millions and paid in millions. One must ask oneself the question in our society, can any painting be worth the total yearly income of a thousand families?

And if we must answer that it is -- and the auction reports tell us so -- then I think we are forced to consider the possibility that the art on which we nourish ourselves is sapping our vitality and breaking our hearts.

But the problem is very deeply seated, as you can see. I'm agitated in this situation because of the concept I have of the importance of the artist, because of my own instinctive respect for him. Is it possible that the way of the masculine artist in our society is strewn with the husks of people worn out and dried out by his ego? Is it possible that all those that have fallen away -- all those competing egos -- were insufficiently masculine to stay the course?

In her essay "My Mailer Problem," published in Esquire shortly after the Town Hall panel, Greer brings this high-flown eloquence down to earth as a series of digs at Mailer. "More killer than creator" alludes to Mailer's "notion of the artist as a great general" (and possibly his pocket knife stabbing of his second wife, although Greer doesn't say it). "Read by millions" Greer translates after the fact as "How does that grab you, Superhack?" "Husks of people worn out" refers to Mailer's fourth wife Beverley, an actress.

I turn for some information to Freud, treating Freud's description of the artist as an ad hoc description of the artist's psyche in our society and not as in any way a metaphysical or eternal pronouncement about what art might mean. And what Freud said, of course, has irritated many artists who've had the misfortune to see it: "He longs to attain to honor, power, riches, fame and the love of women, but he lacks the means of achieving these gratifications." As an eccentric little girl who thought it might be worthwhile after all to be a poet, coming across these words for the first time was a severe check. The blandness of Freud's assumption that the artist was a man sent me back into myself to consider whether or not the proposition was reversible. Could a female artist be driven by the desire for riches, fame and the love of men?

And all too soon it was very clear that the female artist's own achievements will disqualify her for the love of men, that no woman yet has been loved for her poetry. And we love men for their achievements all the time, what can this be? Can this be a natural order that wastes so much power, that frets a little girl's heart to pieces? I had no answers, except that I knew the argument was irreversible. And so I turned later to the function of women vis-à-vis art as we know it, and I found that it fell into two parts, that we were either low sloppy creatures or menials or we were goddesses. Or worst of all we were meant to be both, which meant that we broke our hearts trying to keep our aprons clean.

The goddesses/low sloppy creatures dichotomy is from Mailer's The Prisoner of Sex essay.

Sylvia Plath's greatest poetry was sometimes conceived while she was baking bread, she was such a perfectionist -- and ultimately such a fool. The trouble is of course that the role of the goddess -- the role of the glory and the grandeur of the female in the universe -- exists in the fantasies of male artists and no woman can ever draw it to her heart for comfort. But the role of menial unfortunately is real and that she knows because she tastes it every day. So the barbaric yawp of utter adoration for the power and the glory and the grandeur of the female in the universe is uttered at the expense of the particular living woman every time.

And because we can be neither one nor the other with any peace of mind, because we are unfortunately improper goddesses and unwilling menials, there is a battle waged between us. And after all in the description of this battle maybe I find the justification of my idea that the achievement of the male artistic ego is at my expense for I find that the battle is dearer to him than the peace would ever be. "The eternal battle with women both sharpens our resistance, develops our strength, enlarges the scope of our cultural achievements." So is the scope, after all, worth it? Again the same question, just as if we were talking of the income of a thousand families for a whole year.

Regarding the "eternal battle..." Greer said she read it aloud in her "quoting voice." Did Mailer actually say this? (Haven't found the quote yet.)

You see, I strongly suspect that when this revolution takes place, art will no longer be distinguished by its rarity, or its expense, or its inaccessibility, or the extraordinary way in which it is marketed, it will be the prerogative of all of us and we will do it as those artists did whom Freud understood not at all, the artists who made the Cathedral of Chartres or the mosaics of Byzantine, the artists who had no ego and no name.

As Greer was sitting down Mailer had a quick comeback to this last paragraph: "The sentiments were exquisite. But the means you offer, and in fact that Women's Liberation offers, to go from here to that point where we will be artists all, belongs to a species of social instrumentality that I call 'diaper Marxism.." In Esquire Greer replied "As an old anarchist I take that as a compliment. The infancy of Marxism is profoundly more relevant than anything since betrayed."

The Aftermath of the Panel

After the Town Hall event Greer and Mailer went to court over the rights to the panel's content. Greer is rather vague and arch about it in her Esquire article but here's what we can glean: The event took place under the banner of Theatre of Ideas, which had produced similar evenings of intellectual debate. Transcripts and other documentation were normally published by McGraw Hill. Mailer (or his agents) orchestrated the panel and convinced Theatre to give him the book rights (via New American Library) as well as film; Mailer hired D.A. Pennebaker to shoot it. Mailer planned a media campaign to promote the project, including an appearance on the David Susskind show with Greer.

Greer, meanwhile, had a BBC film crew shooting the event in connection with a "tour of America" she was doing to promote her career as a writer. Panelist Diana Trilling noted in her post-panel memoir (almost everyone involved published one of these) that prior to going onstage, Greer and Mailer posed together for the BBC holding up a copy of The Female Eunuch.

Mailer finessed the issue of monetary compensation for the panel's women participants, as Greer tells it, possibly through a one-time payment to Theatre of Ideas to be shared out among the panelists. Panelist Jill Johnston, in her post panel memoir, says she was never paid. The matter "passed into the hands of" McGraw-Hill's attorneys (Greer says they were representing her interests) and Mailer's projects were delayed. At the end of the Esquire article Greer says the film consisted of reels that "no one has any right to use."

Sometime after the Esquire piece, a settlement of the dispute over rights must have occurred. According to IMDb, filmmaker Chris Hegedus initiated Town Bloody Hall, the film, in the mid'70s, using Pennebaker's footage. The film's IMDb entry doesn't mention the suit and states that "the rushes were consigned to the filmmaker's vaults as unusable after their initial viewing." Town Bloody Hall was eventually released, in 1979. It's intriguing to consider how this bit of intellectual history would be viewed if Mailer had retained the final cut.

(For links to sources please see the previous post. In the 2013 Town Bloody Hall re-enactment event discussed there, moderator Stephanie Frank describes the Greer-Mailer legal wrangling as a "lawsuit" and we've been referring to it as a "court case." Further research would need to be done to see if an actual record exists in the New York courts; possibly the dispute never advanced beyond the stage of lawyers issuing demands.)