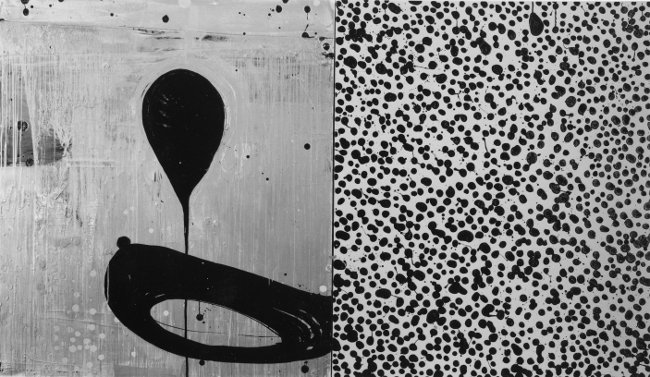

John Pomara, 96 Tears

oil and enamel on canvas

72 x 124 inches

photo: Harrison Evans

larger view

Below is a corrected "author's cut" of a review that originally appeared in Artforum, in December 1991. A post noting the changes was put up previously.

Dallas Reviews, December 1991

John Pomara

EUGENE BINDER GALLERYIn John Pomara’s paintings from the first half of the ’80s, turbulent color fields surrounded silhouetted black abstract forms, evoking robots and spaceships. The science fictional elements combined with graffiti and neo-Expressionist iconography to comment obliquely on the failed aspirations of both mid-century science (Sputnik gone awry) and the artistic would-be heroism of the Abstract Expressionists. The painterly brio of Pomara’s brushwork competed with the dopey, out-of-kilter robotic forms, suggesting a paradox -- the investment of substantial physical energy in the depiction of entropy and collapse.

As the art of the ’80s cooled down, so did Pomara’s, but without abandoning its basic themes or its commitment to paint. The entropic forms remained, but the full-spectrum color and diagrammatic scribblings of the surrounding fields gave way to starker, more subtle painterly effects. As if to compensate for the change, Pomara began to place second panels -- typically fields of dots or organic blobs -- adjacent to the figure-ground studies. On the whole, the added panels suggest a more upbeat approach to art and science than their companions do. Here an interest in investigating patterns of chaos joins Pomara’s characteristic skepticism and taste for paradox.

The new diptychs create dialogues (never simplistic dichotomies) between high and low, macro and micro, esthetic and antiesthetic. The vertical line separating each pair of panels becomes a permeable membrane allowing ideas, motifs, and colors to pass between the rectangles, unifying the paintings and subverting the usual cliches of the diptych format. Assonant and dissonant approaches to the double image appear, respectively, in two large works: Untitled #5 -- Orange, 1991, and 96 Tears, 1990. In the former, aluminum radiator paint is streaked laterally across both panels in a manner recalling photocopies or Andy Warhol’s silk screens. In the left-hand panel, horizontal bands of orange blur the outlines of a skewed, malevolent “spaceship.” In the right-hand panel, dots of orange and black are scattered across a silvery void. The two panels suggest oppositions (portrait and landscape, low culture and high, the ridiculous and the sublime), yet each incorporates formal and thematic elements of the other.

96 Tears presents a more straightforward dichotomy. The aluminum paint on the left side creates a complex, rather nasty surface of welts, drips, and over-painted “mistakes,” the perfect ground for the mutated machine forms. The leopard-skin pattern of black blobs over incandescent yellow in the right-hand panel dazzles and seduces; in fact, one almost wishes to see it isolated. A fine spray of yellow and black dots on the left side maintains an uneasy unity between the canvases.

In some ways, the paintings resemble embryonic cells on the verge of mitosis: one imagines that they could easily split into equally viable bodies of work. That we accept them in this poised state comments on our own divided loyalties: between the need for complexity and a desire for reassuring unities; between our demand for heroism and purity and our doubts that these ideals are attainable.

—Tom Moody